A trip to Japan would not be complete without a little sake tasting! But unless you are an avid sake drinker, it can be hard to know where to begin.

To help you navigate the world of sake, we’ve done plenty of research in Japan: from consulting with sake experts, to the arduous task of tasting sake throughout the country.

We hope our Sake 101 guide helps you get the most out of your next sake experience!

Originally written in 2014, this post was updated and republished on April 2, 2018.

Sake 101

What is sake? When you ask this question in Japan and then in the rest of the world, you’ll get two different answers.

In English, “sake” refers to the alcoholic fermented rice beverage from Japan that you’ve probably sampled at your local izakaya (or local sake bar, if you’re lucky!).

But ask for “sake” in Japan and you may be met with a questioning look. Why is that? Because in Japanese, “sake” refers to all alcoholic drinks in general. That includes beer, wine, whisky, shochu, and the beverage we call “sake” in English.

So what do the Japanese call “sake”? In Japanese, the word for what we refer to as sake is nihonshu. Nihonshu translates as “Japanese alcohol,” and if you ask for nihonshu at an izakaya, you will be greeted with a smile.

Language lesson aside, we will be referring to this wonderful beverage as sake in this article to keep things as simple as possible.

Key Sake Terms

One of the best things about sake is that there are so many different types and variations — but this variety is also overwhelming to sake newbies!

If you want to become a sake samurai, you’ll need to go to sake school. But if you want to start with the basics, here are some key concepts and terms that will help you wrap your head around this delicious drink.

Polishing

One of the first steps in sake making is the polishing of the rice. Prior to the actual sake-making process, the rice kernel has to be “polished” — or milled — to remove the outer layer of each grain, exposing its starchy core.

To get some perspective on rice polishing, keep in mind that to get from brown rice to white rice, you need to polish rice to about 90 percent (i.e., polishing off 10 percent).

To produce good sake, you need to polish off much more than that! We’ll get into a little more detail below, but for now keep in mind that good sake is usually polished to about 50 to 70 percent (i.e., from 30 to 50 percent is polished off). So if you read that a sake has been polished to 60 percent, it means 40 percent of the original rice kernel has been polished away, leaving it just 60 percent of its original size.

The more rice has been polished, the higher the classification level. But more polished rice doesn’t always mean better rice. Sake experts also love the cheaper local stuff, as long as it’s made from quality ingredients by good brewers. Ultimately, you should trust your own palate and preferences.

Junmai

Junmai is the Japanese word meaning “pure rice.” This is an important term in the world of sake, as it separates pure rice sake from non-pure rice sake.

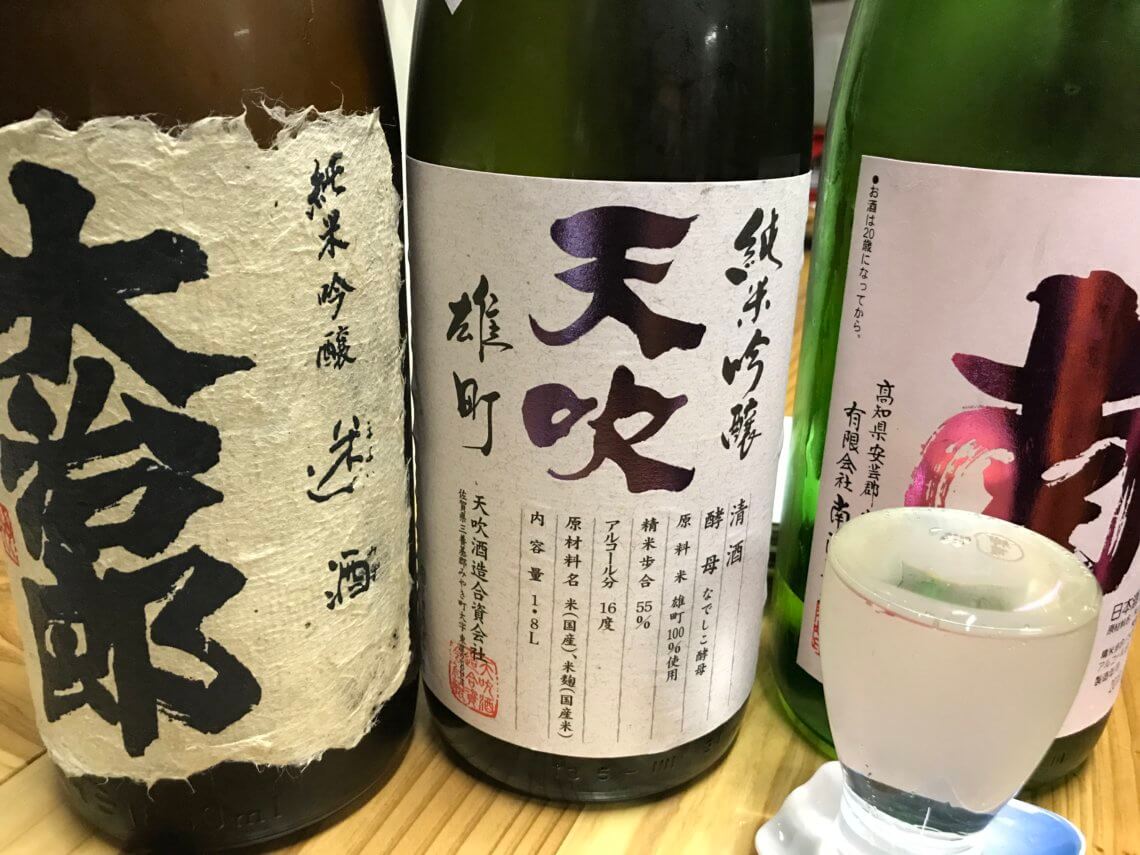

Junmai is brewed using only rice, water, yeast, and koji — there are no other additives, such as sugar or alcohol. Unless a bottle of sake says “junmai” (this will be written in Japanese as 純米), it will have added brewers alcohol and/or other additives.

While junmai sounds like a good thing (and it usually is!), just because a sake is not junmai does not mean it is inferior. Additives such as distilled brewers alcohol are used by skilled brewers to change and enhance flavor profiles and aromas, and can make for some very smooth and easy-to-drink sake.

Now that you’ve learned what polishing and junmai mean, let’s talk about the different types of sake.

Types of Sake

Your understanding of polishing and junmai (from above) will help you see the differences between the various types of sake.

There are so many different types of sake that — to keep things simple — we’re going to focus only on some major types and classifications. Along with a good cup, this information is all you need to enjoy some sake tasting at a specialty sake shop, bar, or izakaya.

You can classify sake by several factors, including the type of rice used, where it was produced, the degree to which the rice has been polished, brewing processes, how it was filtered, and more.

We want you to enjoy sake tasting — not overwhelm you — so here is a handy list of the main types and classifications of sake you will encounter.

Different types of sake (read more about each below):

- Junmai

- Honjozo

- Ginjo and Junmai Ginjo

- Daiginjo and Junmai Daiginjo

- Futsushu

- Shiboritate

- Nama-zake

- Nigori

- Jizake

If you learn even just a few of these, you will know more about sake than 99 percent of the travelers who visit Japan.

Junmai

Junmai refers to pure rice (純米) (non-additive) sake. The only ingredients used are water, rice, koji and yeast – with no added alcohol. This classification also means that the rice used has been polished to at least 70 percent. Junmai sake tends to have a rich, full body with an intense, slightly acidic flavor.

Honjozo

Honjozo (本醸造) also uses rice that has been polished to at least 70 percent (as with junmai). However, honjozo, by definition, contains a small amount of distilled brewers alcohol, which is added to smooth out the flavor and aroma of the sake. Honjozo sakes are often light and easy to drink, and can be enjoyed both warm or chilled.

Ginjo and Junmai Ginjo

Ginjo (吟醸) is premium sake that uses rice that has been polished to at least 60 percent. It is brewed using special yeast and fermentation techniques. The result is often a light, fruity, and complex flavor that is usually quite fragrant. It’s easy to drink and often (though certainly not as a rule) served chilled. Junmai ginjo is simply ginjo sake that also fits the “pure rice” (no additives) definition.

Daiginjo and Junmai Daiginjo

Daiginjo (大吟醸) is super premium sake (hence the “dai,” or “big”) and is regarded by many as the pinnacle of the brewer’s art. It requires precise brewing methods and uses rice that has been polished all the way down to at least 50 percent. Daiginjo sakes are often relatively pricey and are usually served chilled to bring out their nice light, complex flavors and aromas. Junmai daiginjo is simply daiginjo sake that also fits the “pure rice” (no additives) definition.

Futsushu

Futsushu (普通種) is sometimes referred to as table sake. The rice has barely been polished (somewhere between 70 and 93 percent), and — while we’re definitely not qualified to be sake snobs — is the only stuff we would probably recommend staying away from. Surprisingly, you can get really good-quality sake for very reasonable prices, so unless you’re looking for a bad hangover (and not-so-special flavor), stay away from futsushu.

Fewer Clients, Richer Experiences

We live and breathe Japan, and want you to experience the Japan we know and love. If you’re as obsessed with the details as we are, chances are we will be a good fit.

Shiboritate

Although sake is not generally aged like wine, it’s usually allowed to mature for around six months or more while the flavors mellow out. However, shiboritate (しぼりたて) sake goes directly from the presses into the bottles and out to market. (People generally either love it or hate it.) Shiboritate sake tends to be wild and fruity, and some drinkers even liken it to white wine.

Nama-zake

Most sake is pasteurized twice: once just after brewing, and once more before shipping. Nama-zake (生酒) is unique in that it is unpasteurized, and as such it has to be refrigerated to be kept fresh. While it of course also depends on other factors, it often has a fresh, fruity flavor with a sweet aroma.

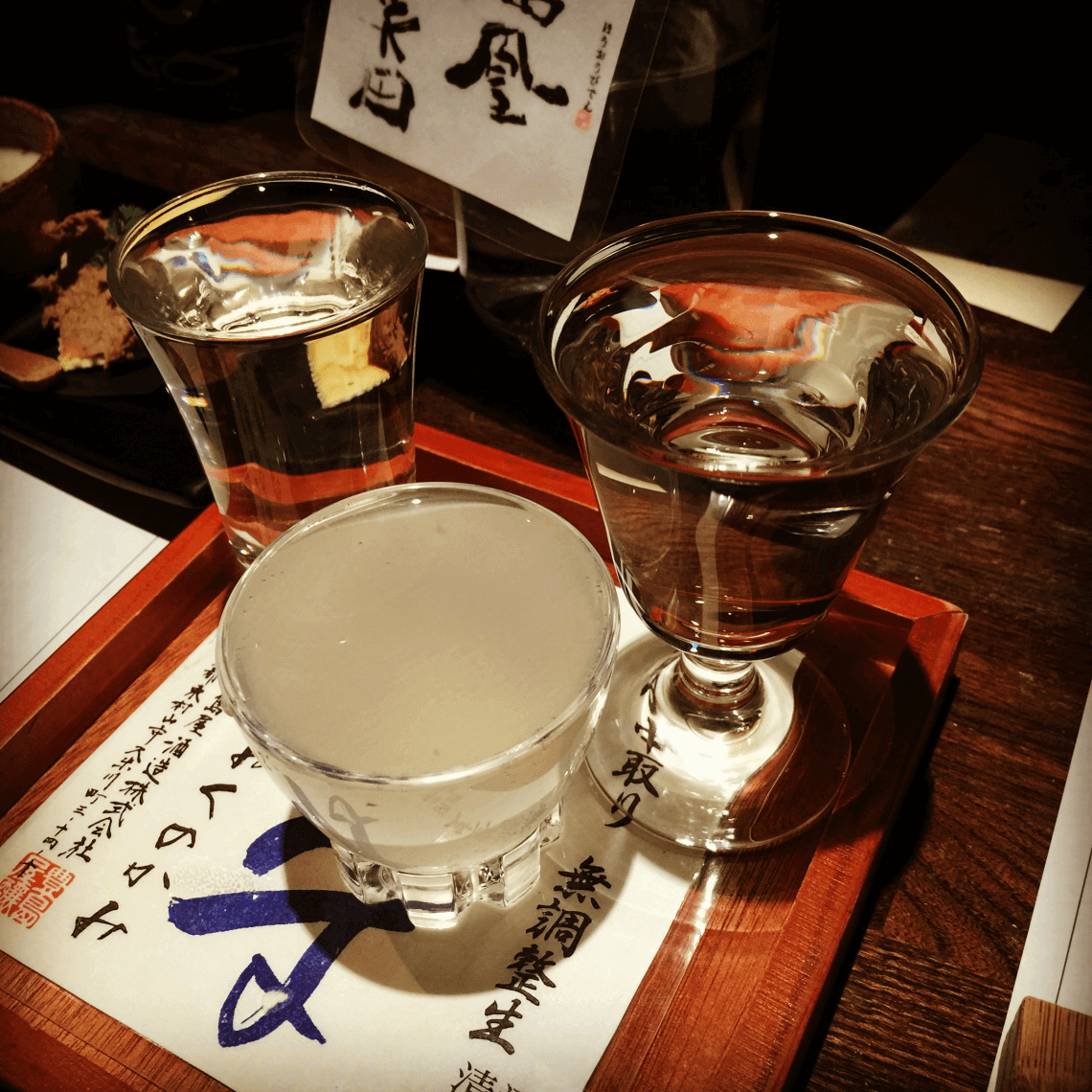

Nigori

Nigori (濁り) sake is cloudy white and coarsely filtered with very small bits of rice floating around in it. It’s usually sweet and creamy, and can range from silky smooth to thick and chunky. This type of sake seems to be far more popular in Japanese restaurants outside of Japan than in Japan.

Jizake

Jizake (地酒) means “local sake” and is a great word to keep in mind when traveling to different regions of Japan. Sake is brewed throughout the country, and good jizake usually goes extremely well with each region’s local cuisine — and since it’s local, it’s also usually fresh and often nicely priced.

Please remember, these tasting guidelines are designed to provide a baseline introduction to sake. There are many factors that can change the characteristics of any sake (the rice and water used, skill of the brewers, etc.), so please expect variations when it comes to each sake’s profile. Keep an open mind as you try different sakes, just as you would when overcoming sushi myths.

How to Drink Sake

Now comes the fun part and final step: drinking the sake! The most common questions we hear from sake beginners are:

- Should you drink sake cold, warm, or at room temperature?

- What kind of cup or glass should you drink it out of?

To Chill or Not to Chill

There is no hard-and-fast rule, and the most important considerations are the particular sake in question and your own preferences.

Some sake is at its best cold, while others taste perfect when warmed. Every sake is different, and sake connoisseurs will tell you to experiment. Our philosophy is: Do what tastes best to you. It’s no fun if you’re worried about whether what you’re doing is right or wrong.

That being said, here are some general guidelines to help you in knowing whether to cool or warm sake:

- Ask the shop or restaurant staff for their recommendation: They will know whether it is best cold, warm, or either way.

- Avoid extremes: Whether chilling or warming, be careful not to overdo it, since overheating and over-chilling can disrupt a sake’s particular flavors and aromas.

- If warming, don’t heat the sake directly. Rather, pour the sake into a receptacle (like a sake carafe, ideally) that can handle some heat, and then heat it very gradually in a water bath. Avoid heating it too quickly or too intensely (definitely don’t do it in a microwave!).

- At the risk of overgeneralizing, many sake experts say that ginjo and daiginjo sakes are usually best not warmed (since being served chilled enhances their flavors and aromas), while many junmai and honjozo sakes do well either way (since warming these types of sakes tends to draw out their complex flavors and smooth them out a bit).

Many sake varieties taste great at different temperatures — as different temperatures draw out distinctive characteristics — which makes it very worthwhile to experiment for yourself.

What Kind of Receptacle to Use

We wish we could tell you that all sake experts agree, but of course, this is never the case.

With premium sakes, many connoisseurs recommend drinking sake out of a glass, as this tends to avoid getting in the way of the complex and often subtle flavors and aromas. But it’s also fun to drink sake out of an ochoko or masu, and enjoying the sake receptacle itself can greatly enhance the experience.

If you do have a more delicate palate and can deeply appreciate sake’s profound characteristics, then it will be worthwhile to invest in good sake-drinking glasses.

As with everything else, the golden rule is not to take things too seriously, and enjoy yourself!

What Next?

The best way to really gain an appreciation for and understanding of sake is to drink it. So get out there and taste some sake — you may be surprised to find you have a particular type, style, and temperature you like best.

We offer sake-tasting experiences with local sake connoisseurs in Tokyo, Kyoto, and throughout Japan, as well as occasional sake brewery tours.

Kanpai (cheers)!